Shelby Weaver (U.S., b. 1953) is a Utah outsider artist in a state where outsider has special meaning. He grew up in the small northern Utah town of Hooper. When asked what made him want to make art, he replied, “It was clouds, seeing shapes in clouds, saying, I could make those – my mother all the while hanging laundry on the line.”

Weaver’s keen visual attunement comes more from observing life than fitting into any formal discipline. He is truly self-taught. When he was about eight, he covered a bunch of nightcrawlers with wild-colored paints and set them loose on a sheet of Masonite. As they wiggled and writhed, they created the painting. He has always given them artistic credit.

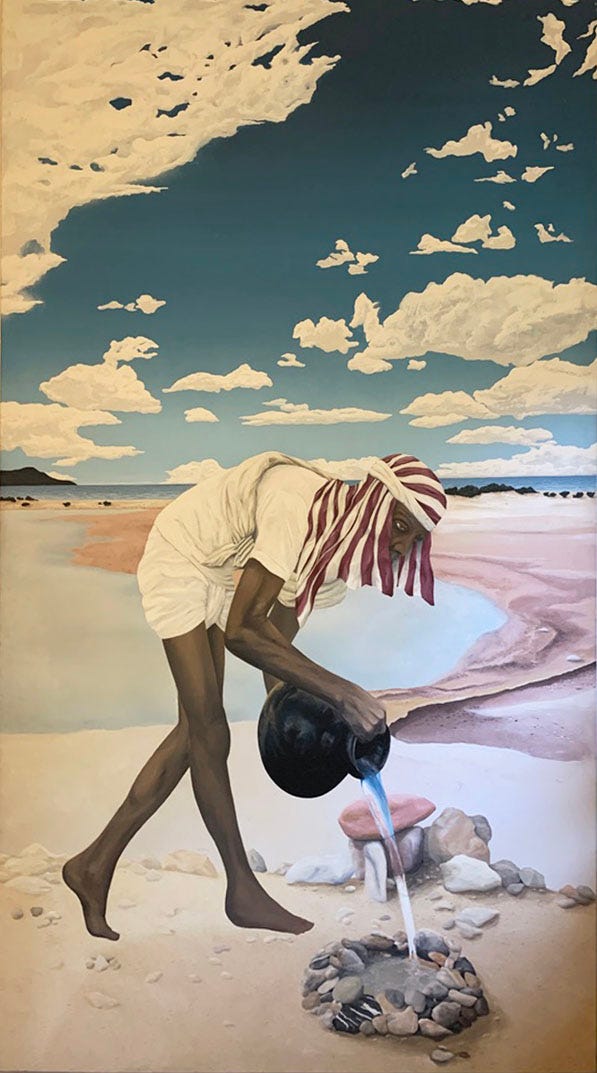

In his mid-twenties, he embarked on a five-month solo journey through Europe and the Middle East, ending up in India. Once he returned home, he continued to wear the loose-fitting Arabic clothing and turban he adopted on the road. He says the travels left him both edified and broken. The monumental paintings in this exhibit come from that period of his life and are full of wonder and pain.

He has always created paintings, drawings and sculpture though having to make a living limited his time and funds for supplies. For years, he refinished antique pianos and fine furniture. Bringing wood back to life was a joy but breathing lacquers and solvents permanently compromised his health.

Health challenges brought Shelby and his wife, Theda, to Virgin, Utah in 2010 where they eventually moved onto an old farmstead. Many of his found-object sculptures were created out of rusted metal and old machine parts that had been discarded on the property. Theda passed away in July 2021. Since then, Shelby has jettisoned most of his worldly possession and lives a monk-like existence. He refers to himself as an introvert isolationist. These days he finds joy in watching fine classic films and listening to a diverse array of music.

I wrote these words for an exhibit that opens tonight at the Southern Utah Museum of Art’s Rocki Alice Gallery (SUMA) March 30 through May 18. This will be the first retrospective of Shelby Weaver’s paintings, with a smattering of his sculptures. I’ll proclaim here and now that this work is important. You might ask by what authority I make this proclamation? Since I can say anything I want in the Loose Cannon Boost, I’ll say it and suffer the consequences later, maybe even on Judgment Day. By the way, is it scheduled yet on the cosmic calendar?

The Visit

Today I’m visiting Shelby Weaver. Whenever I phone him, I get the feeling he’d rather be left alone. Even so, I know there is a bond of trust between us. I persevere. We need to see this exhibit through. Today, I’m on a mission. I realize that we don’t have any photographs of the artist. I figure SUMA should see what he looks like since they now hold his paintings in their permanent collection. I’m hoping I can cajole him to see the exhibit but I have my doubts. I’ll tell the story of how this exhibit came to be later.

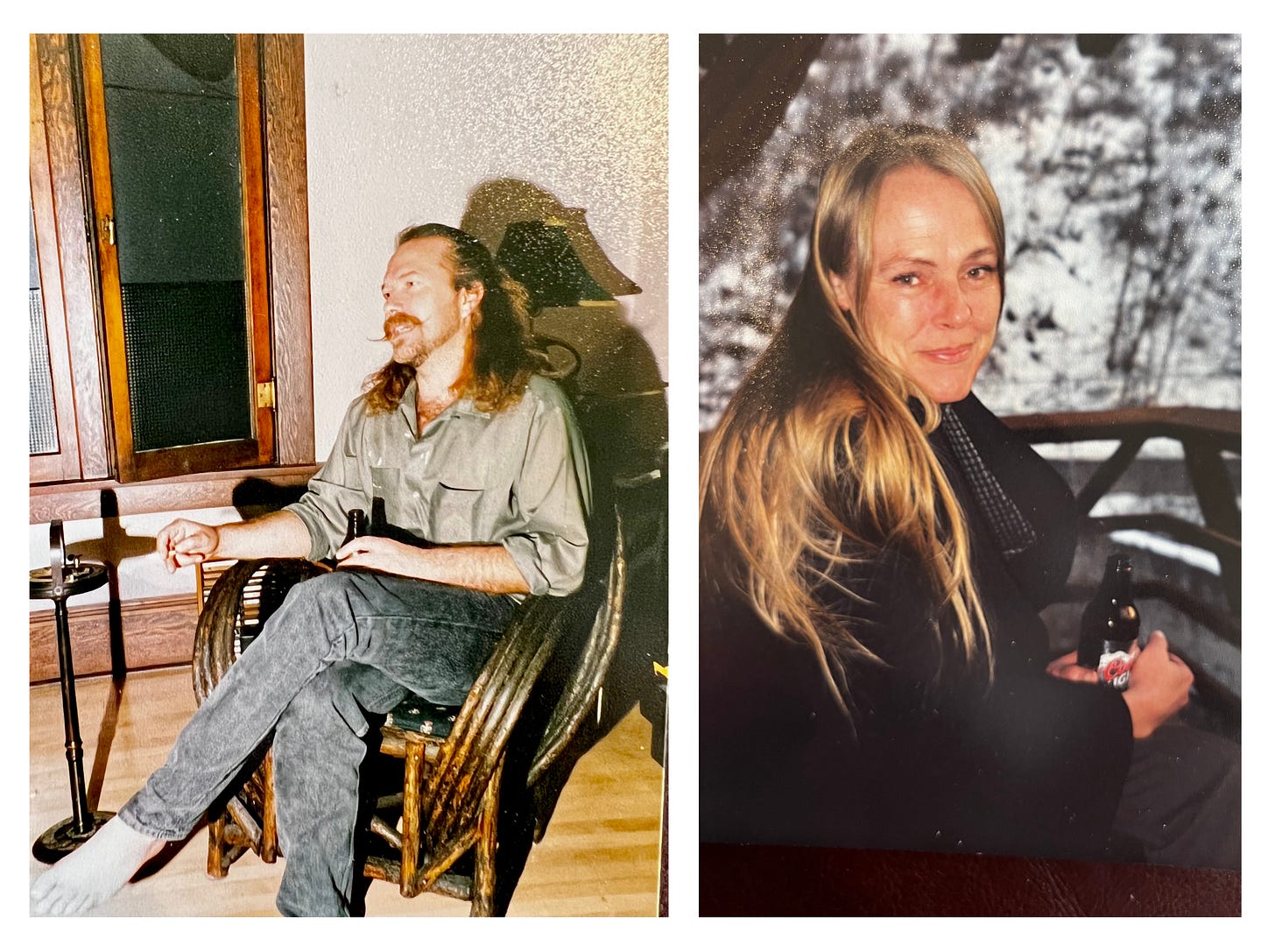

When I get to his house he shows me two photos, one of him in his younger days and the other of his late wife, Theda. He looks up as though he has no control over his defiant face and says, “Yea, I had hundreds of pictures of us. These are the only two I kept.” I handle them carefully.

I ask if he minds me snapping some photos as we sit and talk. He agrees. We sit in his living room--I’m on a leather couch, he’s on a matching easy chair. The stereo plays behind us. We both sit looking towards the front door, north light diffused. The walls are bare. Shelby lives in a clean house. It looks like he just moved in or is about to move out. Every time I ask him what he’s been doing he says he’s been shopping, mostly on the lookout for good films on DVD which he can often buy two for $5. I can’t say what he does the rest of the time. My guess is that contemplation is his occupation. Perhaps it has always been his occupation though once, when he listed all the different jobs he held over the years for me, they were diverse.

Besides movies, Shelby loves music and this day he is listening to David Bowie’s “Reality.” As we listen, he tells me about the impressive breadth of Bowie’s music. I’m not hearing it, but I vow to listen more carefully and with more respect on some future day. He suggests other Bowie albums, Earthling and Heathen. I make a mental note. I trust Shelby’s ear for music.

Lately, I’ve been on an intense Nick Cave jag and ordered a copy of Cave’s album Carnage for Shelby. Now I wish I would have ordered Ghosteen. I sheepishly ask if he received the CD. I can tell immediately he doesn’t want to hurt my feelings, but truth is in his face. He replies, “Sometimes I’m into God music.” I mutter something about the spiritual and he looks at me with another of those looks he can’t help. This one says, “you dumb shit.” Then he gently exclaims, “Spiritual can mean about anything.” We leave it at that.

Now that he’s making recommendations of music for my edification, he suggests a couple of films including the 1982 Flight of the Eagle with Max von Sydow. He tells me the film is based on a tragic balloon expedition in 1897 that ends in disaster. North Pole exploration has always fascinated him.

I do an online search on my phone for the title but none of my streaming services list it. I’m reminded again how vast and yet incomplete the digital world is. I almost envy Shelby for never succumbing to computers and the message most of us have come to accept: if you can’t find it on the internet, it must not be meaningful.

Looking back at the photographs I took today I realize Shelby has an unnervingly expressive face. So many of Shelby’s expressions expose the irony of life. It’s all about beauty and pain. I know he is both a loner and painfully lonely.

I can’t quite figure out my bond to Shelby. We didn’t know each other growing up and never ran in the same circles. But we noticed many of the same things in our youthful explorations.

Once I mentioned the Wardle Barbershop near downtown Salt Lake City. Immediately, Shelby volunteered, “Heresy Spoken Here.” Those were going to be my next words had he given me a chance. Indeed, that was a small sign in the kooky barber’s window and it was what attracted me to walk in for haircuts from this eccentric religious-scholar barber when I was twenty years old. Somehow Shelby keyed into the same oddities.

How We Became Trustees of Shelby’s Art

I’m not sure if Teresa and I inherited Shelby Weaver or he inherited us. When we purchased our home in an old pioneer pecan orchard in Virgin, Utah, Shelby and Theda became our tenants. It was awkward because our intention was to combine the two halves of the rental duplex into a single home for ourselves. We were clear about this when we made the offer. but it meant the Weavers would need to find a new place to live. As I remember they were with us for about six months before the remodel started.

Regardless, Shelby and I struck up a friendship right away. At the time of the purchase, Teresa and I lived in a doublewide a few houses away, and I had noticed Shelby sitting in a lawn chair early each morning, winter and summer, a Coors Light by his side and a smoke in his hand. Though I had never met him, his daily pose never appeared frivolous. Shelby looked to be in deep concentration.

It wasn’t long before I was lending Shelby favorite CDs and he was introducing me to his music collection. He was also in the midst of creating metal sculptures from a vast rusty junk yard next door. I learned quickly that Shelby had a substantial reservoir of art and creativity in his soul. I also noticed that he was functionally drunk most of the time. I should mention it’s been a year since Shelby has had a drink or a smoke. If anything, he’s more intense than ever.

At some point Shelby and Theda moved and I did not see him as much even though they were only five miles away in the next town. One day in 2015 he called with a surprising offer. He explained that Theda had experienced a hard winter and that he had suffered a second stroke. He went on to tell me that one of his great fears was to die with the landlord taking his art and his collected treasures to the dump or to Deseret Industries (a chain of thrift stores run by the LDS Church, something like Goodwill stores elsewhere). He asked if we would come and get his art collection. It was a surprising request, but he explained that we were practically his only friends in the area.

When we arrived to see the collection, he showed us a garage full of metal sculptures, a half dozen immense canvases that were carefully wrapped in foam protection, boxes of books and papers, and some amazing antique ethnic musical instruments he had collected in his travels to the Middle East. There was also an extraordinary vintage slide guitar called a Weissenborn which I immediately fell in love with.

We could tell the paintings were particularly dear to Shelby. He told us that since he made the paintings in the late 70s he had moved and stored them in many places. I could tell he considered them the core of his accomplishment. Over the years he’d given away a few paintings randomly, mostly to people he hardly knew, but those are now long gone. He wanted the corpus of his work to go with us.

Teresa and I went home perplexed. How could we fit all of this into our already possession-filled life? Yet we also sensed that this was important. We both remember that first night, dreaming together about how wonderful it would be if we could place the collection in a museum. The metal sculptures were a problem. Paintings are much easier to store. The next day we asked Shelby if he would allow us to distribute sculptures to our friends, keeping track of where they ended up, in case we could arrange a museum showing sometime in the future.

Shelby was agreeable and said simply, “These are yours. You can do what you want with them.” He was surprised when we wrote a fairly substantial check, at least within our art budget, something to seal the deal. He later told me the check came at a good time as finances were low and they needed a new car.

The next day I rented a U Haul and we loaded it all up. All but three of the sculptures went to other homes. And for the next five years most of the wall space in our home has been inhabited by five massive paintings. We could never quite wrap our minds around the fact that these belonged to us. We were just caretakers.

Shortly after the new Southern Utah Museum of Art (SUMA) opened, it named a new director, Jessica Kinsey. When Teresa met her, she was impressed by her ambitious plans for the facility. Later, Teresa was invited to join the advisory board. About a year ago, Teresa proposed SUMA consider accessioning Shelby’s paintings into their collection. Southern Utah is known for its landscapes and the paintings that depict them. In fact, much of the impetus for building the new museum was the donation of a collection of painting by a premier Utah landscape artist, Jimmy Jones. When the advisory board crafted a new vision statement for SUMA, they reinforced the commitment to landscape art and also expanded the intent to showcase the full range of Utah art, including outsider art. Teresa thought Weaver’s paintings served that objective.

Eventually Jessica came to our home to see the works. She was enthusiastic and agreed to propose the gift to the accession committee. We were overjoyed when we got the letter of acceptance. In her letter, Jessica shared a comment from a faculty member on the committee who wrote, “I'm grateful to Teresa for thinking of SUMA. Of course, Mr. Weaver's story is an enhancement, but the works (particularly the large paintings and metal sculptures) are original and strong, and their sound, balanced rhythms suggested to me immediately that he was a genuine formalist.”

At this point Shelby was unknown to them and they didn’t even know whether or not he was still alive. Shelby is very much alive and over the past months I have been pestering him, taping interviews, measuring and photographing the art and getting it ready for this day, a day which should have taken place many years ago, where Shelby Weaver’s paintings are shared with the world, at least our small part of it.

Weaver's art is fanciful and surreal, yet strangely human.

Well now, this is a little piece of magic and wonderment!